Products are selected by our editors, we may earn commission from links on this page.

Anne Boleyn’s face has been copied so many times that it can feel more legend than person. Now, new research on one of her most famous portraits suggests the painter was doing more than recording a likeness. Infrared scans reveal a hidden design change that historians say was meant to answer a very specific rumor about the queen’s body and supposed “witchcraft.”

A Queen Buried in Myths

For generations, stories claimed Anne Boleyn had six fingers, a deformed fetus, and even supernatural powers. A feature article from Selly Manor Museum notes that no contemporary source mentions an extra finger and that these details appeared decades later, when hostile writers wanted to blacken her name. Those myths stuck anyway and helped turn Anne into one of the most divisive figures of the Tudor period.

Why a Sixth Finger Mattered So Much

In Tudor England, physical “oddities” carried heavy meaning. The UK Parliament’s overview of witchcraft laws explains that unexplained misfortune and visible anomalies were often blamed on evil spirits, with Parliament eventually making witchcraft a capital crime in the 16th century. An extra finger could be read as a sign of a pact with dark forces, which made Nicholas Sander’s later claim about Anne’s right hand especially damaging in a culture already primed to fear witches.

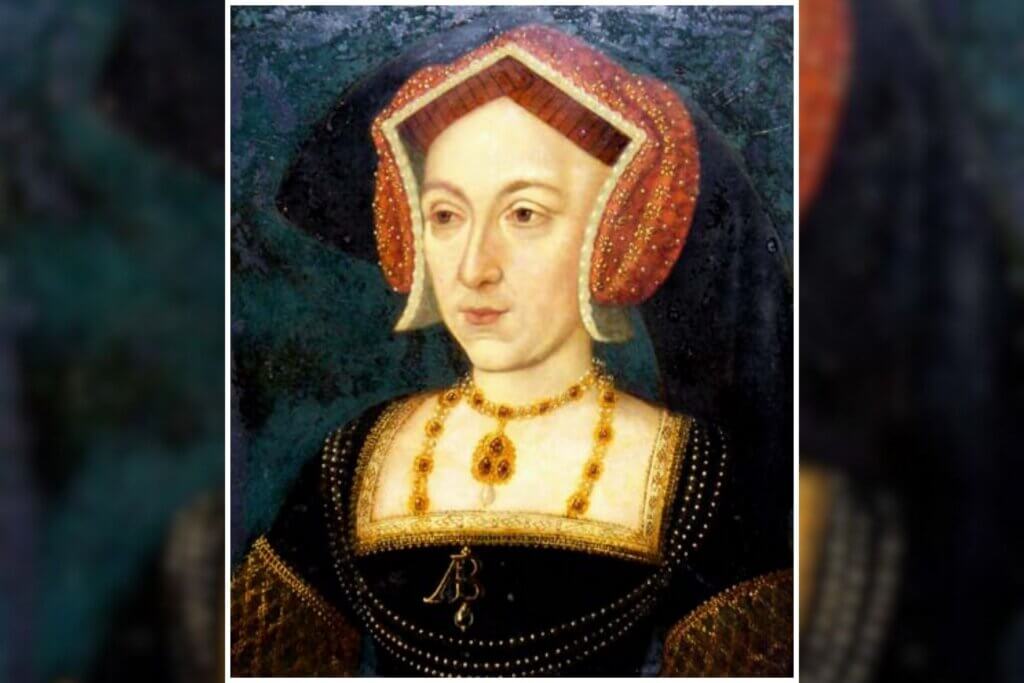

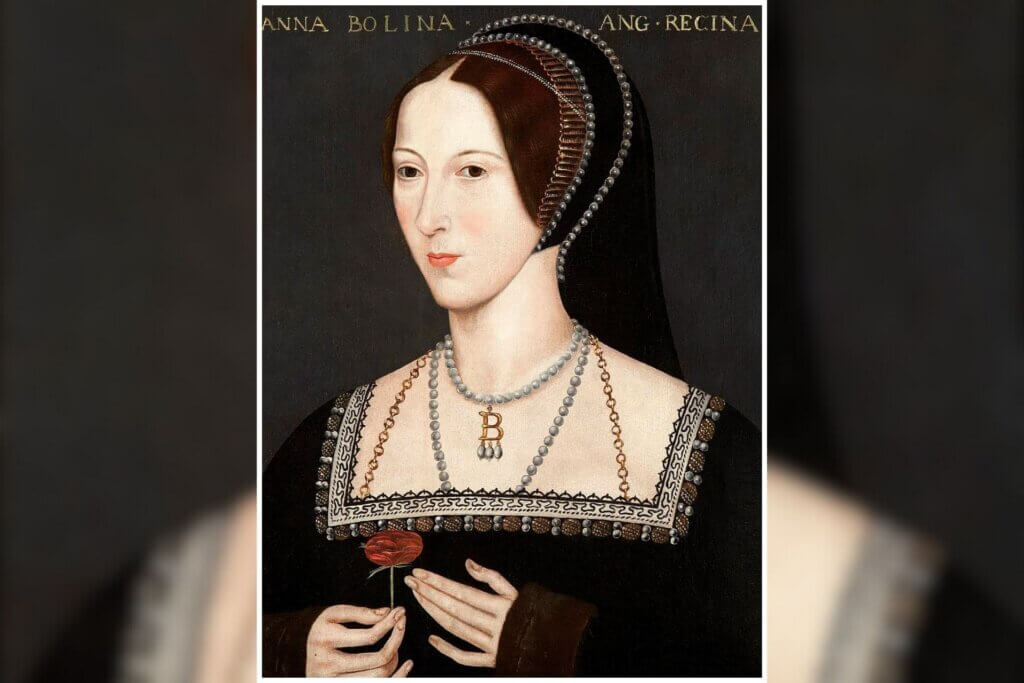

The Hever ‘Rose’ Portrait Under the Spotlight

The portrait at the center of the new research hangs at Hever Castle in Kent, the house where Anne spent part of her childhood. The so-called Hever “Rose” portrait shows her in a French hood, with the famous “B” pendant and a red rose near her right hand. Tree-ring analysis of the oak panel, commissioned by Hever and reported by both Discover Britain and The Guardian, dates the painting to around 1583, during the reign of Anne’s daughter Elizabeth I.

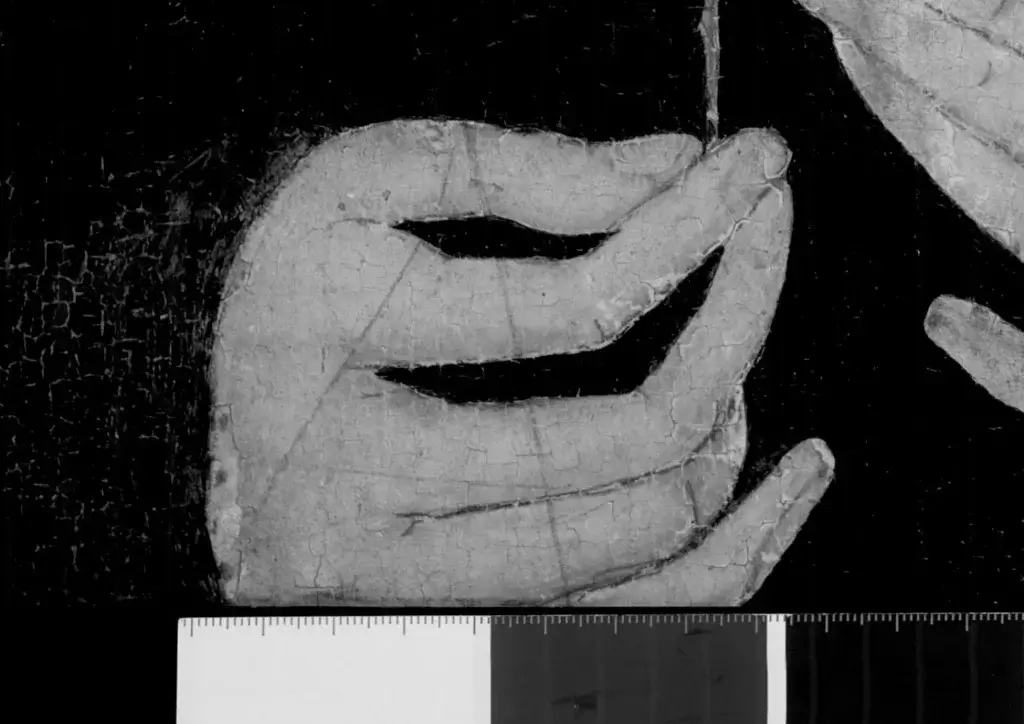

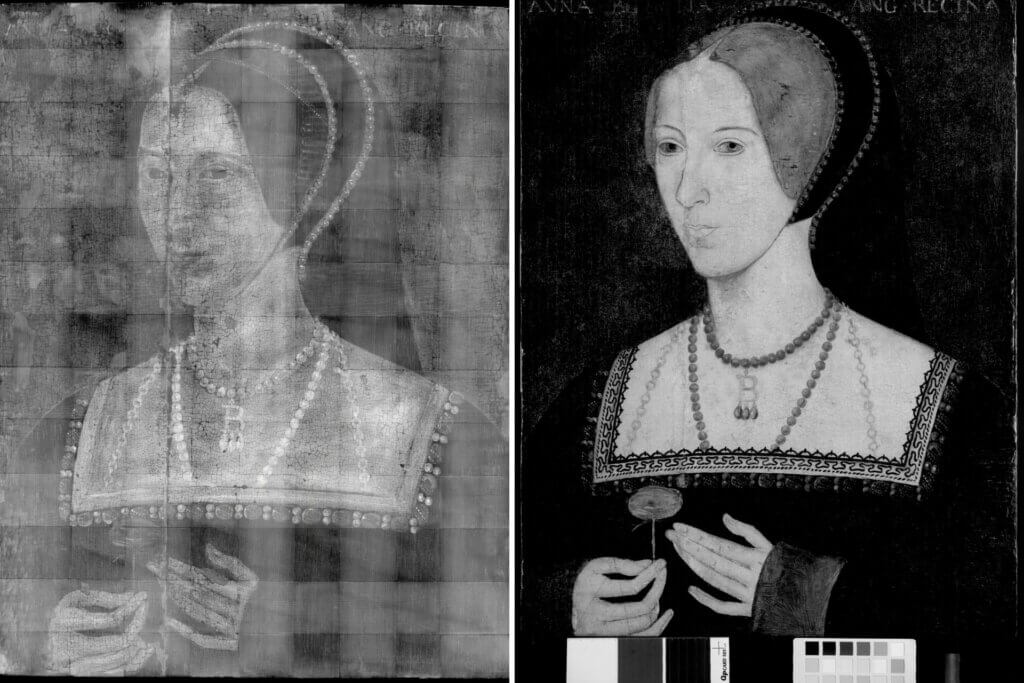

Infrared Scans Reveal a Change of Plan

When conservators used infrared reflectography on the portrait, they found a discarded triangular shape under Anne’s right arm. Researchers at the Hamilton Kerr Institute concluded that the artist initially followed the standard “B pattern” used for many Anne Boleyn portraits, which focused mainly on head and shoulders, and then altered the design mid-way. The reworked composition brings Anne’s hands into full view as she holds the rose, a change that had been invisible to viewers for centuries.

Hands Used as a Quiet Argument

Hever Castle’s assistant curator Dr Owen Emmerson told the BBC that “the decision to show Anne’s hands should be understood as intentional,” describing the finished painting as a “visual rebuttal to hostile rumours” that she had extra fingers. He repeated that view in comments to The Guardian, saying the portrait defends Anne and, by implication, Elizabeth’s legitimacy by clearly showing five digits on each hand. The castle’s own write-up of the research calls the portrait “both a work of art and an argument.”

Where the Witchcraft Story Started

The six-finger rumor can be traced to Nicholas Sander, a Catholic writer who never met Anne but published a hostile account of her in 1585 while campaigning for the restoration of Roman Catholicism. Selly Manor’s article on Tudor Myths shares that Sander described Anne as sallow, snaggle-toothed, and deformed, claiming she had “on her right hand six fingers,” and that his goal was to undermine Elizabeth I by attacking her mother’s character. Discover Britain reports that these details became some of the main “evidence” used to paint Anne as a witch in later retellings.

Elizabethan Politics Behind the Paint

Dating the portrait to 1583 places it in a tense moment of Elizabeth’s reign, when religious conflict and questions about her legitimacy still simmered. Hever Castle’s research team argues that revisiting Anne’s image then was a political act, not just a nostalgic one, at a time when slanders about her body and faith still circulated. The castle’s statement describes the Hever “Rose” portrait as a purposeful Elizabethan reimagining that reshaped a familiar image to answer those rumors.

Historians See a Planned Rebuttal

Historian Helene Harrison, author of The Many Faces of Anne Boleyn, had already suggested that the prominent hands in the portrait were no accident. In an interview quoted by both The Guardian and Discover Britain, she said she was “struck by the possibility” that the artist included them to counter Sander’s six-finger claim and called it “amazing” to see scientific analysis support that theory. For Harrison and the Hever team, the altered underdrawing confirms that the painter went “rogue” on purpose to answer a very specific slur.

Seeing Anne as a Person, Not a Spell

The new findings challenge the long-standing image of Anne as a woman marked by dark forces. Hever Castle’s curators say the portrait, newly dated and reinterpreted, offers a “more human impression” that lines up more closely with contemporary descriptions, which emphasized her intelligence and charisma rather than supernatural traits. An upcoming exhibition at Hever, Capturing a Queen: The Image of Anne Boleyn, now uses the portrait as a centerpiece to show how politics, rumor, and art combined to shape the face people thought they knew.